We Were Preparing for This

Isaac of Nineveh, Syrian Monk wrote, "Silence will unite you to God himself. More than all things love silence: it brings you a fruit that tongue cannot describe. In the beginning we have to force ourselves to be silent. But then there is born something that draws us to silence. May God give you an experience of this "something" that is born of silence. If only you practice this, untold light will dawn on you in consequence. After a while a certain sweetness is born in the heart of this exercise and the body is drawn almost by force to remain in silence." (Merton, Contemplative Prayer, 30).

In mid-March as schools and congregations began to close for what initially appeared to be a two-to-four week hiatus, a business leader friend of mine asked the question, “Did the seminary prepare students for this?” It’s a good question - Who is prepared for this? How do you prepare for this? I pondered the question, “No one is prepared for this - unless you were alive during the Spanish flu.” But I have now come to wonder - were we preparing our students for this?

Over the past week or so I am noticing how I have become numb to this Stay Home experience. I notice that the “19” in Covid-19 harkens to my increased body weight. I notice how I drink at night to curb the growing agitation and anxiety resting in my lower back and between my shoulders. My friend, Chuck DeGroat has noted the desire to numb and the growing metal health crisis elsewhere. What he has analyzed; I am experiencing. My life was growingly unbearable. One night I mentioned to my wife, “I am having a bad day.” She replied (uncharacteristically), “You seem to be having lots of those.” Once I got over my initial anger at her judgment, I realized that she is right. That was my wake up call.

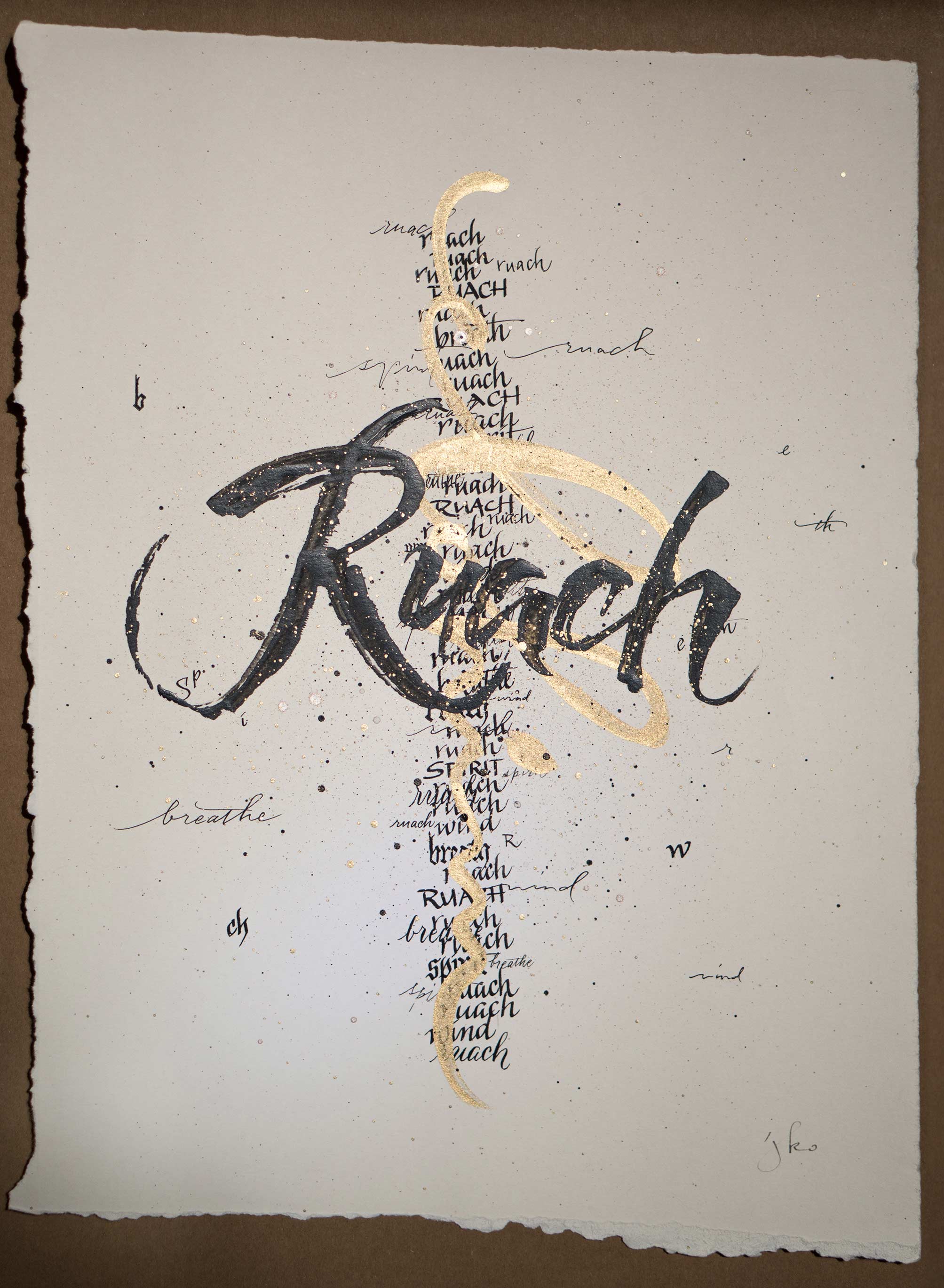

This all took a turn on a recent evening. I was anxious and overwhelmed at the end of the day. I scrolled through the news, which didn’t help. I finally threw down my phone, stood up, and looked outside at the shining sun. I took a big and deep breath and felt the release of pain and tension my body. My shoulders dropped from my ears and my back released, if even for only a moment. I too another slow and deep breath. A few minutes later my wife walked over to me and scratched my back. I could feel the need for connection and intimacy pour life into my weary bones. I closed my eyes and breathed deeply. As I released the air from my lungs, the gravelly sound of ru-ach fell from my lips, and I remembered. I remembered my breath - which is the beginning of remembering the presence of the Spirit.

This all took a turn on a recent evening. I was anxious and overwhelmed at the end of the day. I scrolled through the news, which didn’t help. I finally threw down my phone, stood up, and looked outside at the shining sun. I took a big and deep breath and felt the release of pain and tension my body. My shoulders dropped from my ears and my back released, if even for only a moment. I too another slow and deep breath. A few minutes later my wife walked over to me and scratched my back. I could feel the need for connection and intimacy pour life into my weary bones. I closed my eyes and breathed deeply. As I released the air from my lungs, the gravelly sound of ru-ach fell from my lips, and I remembered. I remembered my breath - which is the beginning of remembering the presence of the Spirit.

In that brief moment, I remembered: I am prepared for this. We prepare for this.

Eight years ago I created a course called the Abbey at Western Theological Seminary. The purpose of the course was to take up Christian discipleship in the academy. This course was to move us from talking about Bible and prayer in order to read the Bible and to pray. I love this course, and I am grateful that it is tethered to the schedule on the first day of the week and adjacent to chapel. I am grateful that WTS has long desired to hold the mind, heart and body together - to integrate the whole person. The course has an interesting rigor; it doesn’t require vast amounts of reading or research, yet students describe it as personally rigorous. It requires the whole person to arrive inclined to meet God, and, as John Weborg writes, "God can be lived with, but not easily" (Weborg, Made Healthy in Ministry for Ministry, 33).

The class is organized around weekly embodiment of spiritual practices (or disciplines). It moves from talking about them to locating them in the body. Embodiment creates grace. By grace, I mean that practicing the practices makes room; grows capacity; participates with God who is the most capacious in all the universe. The practices as grace are preparing one for a life of generosity. Putting this habit in the body during class time seeks to develop persons who can show up in ministry during times of overwhelm and anxiety and remain a presence of grace.

I didn’t know then what I know now. The way we read and pray is preparatory. It is putting practice into the body when the times are dire enough to need renewed presence. The course and its counterparts (the Abbey has four semesters of coursework and internship) are preparing people to enter a places filled with pain, confusion, anger, anxiety, loneliness, and frankly, misery, including our own lives. The course hopes to prepare us to face the world but not be overwhelmed. It is preparing them to remain presence and awake and in service during times like these - a global pandemic.

The central practice of the abbey course is silence. Some want to call it meditation; I prefer centering prayer; others call it Jesus Prayer or Breath Prayer. Regardless, the practice is rooted in the Christian tradition called contemplation. The first form of contemplation, from which Centering Prayer emerges, was meditatio scripturarum or meditation upon Scripture. Much ink has been used to explain it, discount it, and analyze it. But simply put, “The contemplative life is to retain with all one's mind love of God and neighbor but to rest from exterior motion and cleve only to the desire of the Maker, that the mind may now take no pleasure in doing anything, but having spurned all cares may be aglow to see the face of its Creator: so that it already knows how to bear with sorrow the burden of the corruptible flesh, and with all its desires to seek to join hymn-singing choirs of angels, to mingle with the heavenly citizens, and to rejoice at its everlasting incorruption in the sight of God.” (St. Gregory)

The central practice of the abbey course is silence. Some want to call it meditation; I prefer centering prayer; others call it Jesus Prayer or Breath Prayer. Regardless, the practice is rooted in the Christian tradition called contemplation. The first form of contemplation, from which Centering Prayer emerges, was meditatio scripturarum or meditation upon Scripture. Much ink has been used to explain it, discount it, and analyze it. But simply put, “The contemplative life is to retain with all one's mind love of God and neighbor but to rest from exterior motion and cleve only to the desire of the Maker, that the mind may now take no pleasure in doing anything, but having spurned all cares may be aglow to see the face of its Creator: so that it already knows how to bear with sorrow the burden of the corruptible flesh, and with all its desires to seek to join hymn-singing choirs of angels, to mingle with the heavenly citizens, and to rejoice at its everlasting incorruption in the sight of God.” (St. Gregory)

Gordon Cosby, long-time pastor of Church of the Savior in DC, described the particular contemplative practice this way, “The fundamental disposition in centering prayer is opening to God. That’s the main thing—opening to God…. It is a disposition of the servant in the gospel who waited, even though the master of the house had delayed his return until after midnight. So no matter how long God delays coming in the way in which we want God to come, we will wait. If you wait, God will manifest—always will.” It is roughly day 60 of the Michigan Stay Home order. Waiting is hard...

It may sound that St. Gregory and Pastor Cosby are separating the monk and the believer from the world through this practice and asking for inactivity and escape. Thomas Merton offers a helpful response, "Quite the contrary: This is an age that, by its very nature is a time of crisis, of revolution, of struggle, calls for the special searching and questioning which are the work of the monk in his meditation and prayer. For the monk searches not his own heart; he plunges deep into the heart of that world of which he remains a part…. In reality the monk abandons the world only in order to listen more intently to the deepest and most neglected voices that proceed from its inner depth” (Merton, Contemplative Prayer, 23).

The one who understands silence knows how to transcend anxious actions (whether internal anxiety, the fear of wearing of masks in public, the chaos at the Michigan capital, etc.) and face our circumstances with a heavenly perspective, namely one of grace, mercy, and responsibility rather than anxiety, judgment, and reactivity. This is what I am trying to do and what we are trying to invite students to practice at Western Theological Seminary. This is what we are doing for the first 10-15 minutes of each Abbey session. We are engaging St. Gregory’s direction in order to be prepared for ministry in a suffering world. We are following Pastor Gordon’s words to wait upon the Lord. Doing so plunges us full on to the present moment, which includes facing suffering and pain. We can only do so because we are enjoined with the angels hymn-singing chorus.

Merton reminds us that during the Middle Ages monks would spend excessive amounts of time in contemplation and then when they would exit the monastery for ministry, they would do so with lamenting and wailing. The ministry of today needs entry with lamenting and wailing but not overwhelm. In this week alone millions will lose jobs, thousands around the world will die of Covid-19 not to mention the deaths from numerous curable and incurable diseases. Additionally, the sin of racism expanded this week to include #RunningWhileBlack and #SleepingWhileBlack. The death and injustice are overwhelming, yet in contemplation, we can awake from our overwhelm and reconnect to the breath of the One who gives us life. In contemplation we can ground ourselves in Christ that we are able to "bear with sorrow the burden of the corruptible flesh.” The silence we experience allows us to re-enter the noisiness of the suffering world. And we can do so with compassion and mercy. The silence carries us through.

Centering prayer is a practice which largely fails to make sense in the classroom each Monday morning. It often fails to make sense in my daily routine over the past ten years, but this week it made sense. One hour of deep breathing grounded me in something larger than myself; I found communion with the Triune God, who weeps with the weeping and rejoices with the rejoicing. Nothing is resolved. Nothing is fixed. But for a moment this day and its overwhelm and anxiety rest in as I rest in the presence of God through silence.

"Does the seminary prepare people for this?” I don’t know; I really don’t. But for a brief moment, I believe WTS and many seminaries like it (and many congregations, too) have cultivated the Christian practice to accompany disciples of Jesus Christ to be present to their neighbors, their families, and even themselves with the compassion of Christ. This presence is all the more necessary in times like these. I must admit - it has taken a long time to realize that this comes primarily through silence.

Comments

Post a Comment